Express API Validations - A Learning Exercise

When building APIs using exciting technologies such as node.js, express, and NoSQL databases, it’s easy to overlook things that are often enforced when using more mature technologies.

We frequently pair our node.js applications with a schema-less NoSQL database such as MongoDB. This is hugely advantageous since it facilitates agile development where our data models are subject to frequent changes and empowers developers. Despite being liberated from strict schemas, this freedom can pose issues when we need to enforce data constraints. In a traditional RDBMS our schema defines such constraints meaning incorrect or even malicious data is more difficult to plant in the database since it performs data integrity checks. With MongoDB we have no such safety net.

In this blogpost we’ll create a RESTful API using node.js, the express web framework, and MongoDB for data storage. We’ll see how the code validating our API inputs will evolve as we leverage the module system, express’ middleware capabilities, and decouple our validation logic from our route logic.

Other goals include making this API:

- Testable - Avoid hard to test spaghetti code

- Secure - Prevent malformed and/or malicious data passing into our system

- Expressive - Easy to read and understand the code

- Maintainable - Future modifications should not be difficult

Iteration #1 - Plain Old JavaScript

On the surface this task appears trivial, and to an extent it is - expose a POST /users endpoint and move on, right? Take a look at the code below and ask yourself if you want all of your application route handlers to resemble this pattern. Better yet, do you want to have to write unit tests for all of it to make sure you’ve handled all potential edge cases that the JavaScript type system has graced us with?

As time moves on and your application grows in scope and complexity the answer will almost inevitably be “no thanks, I’d rather not deal with those edge cases”. Doing this from scratch requires extra development time, and can be bug prone - even for veteran JavaScript developers. Regardless, the code below demonstrates an implementation for performing validations from scratch for an express application.

const countryCodes = Object.keys(require('country-codes'));

const users = require('lib/dao/user');

function isInt (n) {

return n === parseInt(n, 10)

}

// Need to actually parse the incoming POST data

route.use(require('body-parser').json());

route.post('/users', (req, res, next) => {

let name = req.body.name;

let age = req.body.age;

let country = req.body.country;

if (typeof age !== 'number') {

// since we're nice people we'll try parse the value, from a string such as "6" to an integer 6

age = parseInt(number, 10);

}

if (isNaN(age) || age < 0 || age > 150 || !isInt(age)) {

// either age was not a valid number, integer, or is not in range

return res.status(400).end('"age" must be a valid integer');

}

if (!name || name.length < 2 || name.length > 50) {

// name must be a string between 2 and 50

return res.status(400).end('"name" must be a string with length between 0 and 50');

}

if (!country || typeof country !== 'string' || countryCodes.indexOf(country) === -1) {

// country code must match one of those we know

return res.status(400).end('"country" must be a valid country code string, e.g "US"');

}

users.create({

age: age,

country: country,

name: name

})

.then((result) => res.json(result))

.catch(next);

});There’s a chance, depending on the size of your team and the needs of your applications, that you’d be perfectly happy with this. Those with basic JavaScript knowledge can easily read it, but the validations are tightly coupled to the router which makes them somewhat more cumbersome to unit test than should be necessary, and they’re not portable either. To make unit testing easier, and to facilitate DRY principles we should leverage the node.js module system and place our validations in a module that is loosely coupled with the router.

Iteration #2 - Leverage the Module System

If you have any exposure to node.js you’ve probably heard the term “module” used frequently. Node.js modules are little more than sandboxed JavaScript Objects or Functions (Functions also happen to be Objects) that are stored files that can be loaded by other files for use. Unless you’ve been living under a rock you’ll already know that npmjs.com contains a large repository of such modules that you can easily load into your applications.

Leveraging the this module system makes decoupling code trivial, and has the added benefit of simplifying unit testing your application since the router and validation logic can be tested more effectively if isolated from one another.

After refactoring your code to use the module system you’re likely to end up with code that resembles that shown below.

// this is a function that contains our old validation logic

const validateUser = require('lib/validations/user');

const users = require('lib/dao/user');

route.use(require('body-parser').json());

route.post('/users', (req, res, next) => {

// validates and returns the user object on success

validateUser(req.body)

.then((validData) => users.create(validData))

.then((result) => res.json(result))

.catch((e) => {

if (err.validation) {

// validateUser might reject with an error that has

// a validation property

res.status(400).end(err.validation.message);

} else {

// some other error was raised

next(err);

}

});

});After moving our validation code into a module of its own this implementation is not only cleaner, but the validations are now portable and can be used by other node.js services, or even by a JavaScript fronted application. Neat right!?

Iteration #3 - Use Open Source Validation Modules

Examining the latest code you may feel confident that you’re in a good place, but there’s one thing you should know. While reading the code in Iteration #1, did you notice that we forgot to check typeof name !== ‘string’? This omission means an Array could have been uploaded in for our name parameter if the Array contained between 2 and 50 entries - that’s not good since we’ve no idea what issues that might cause! Worse still, you’ll feel like this fixing the mess it might have caused.

Here’s an example of input that would be considered valid if passed to our flawed validation code from earlier.

{

"name": ["n", "o", "d", "e", ".", "j", "s"],

"age": 8,

"country": "us"

}

Writing validations from scratch is challenging since edge cases of this kind are easy to miss. Sure, you might have written ridiculously thorough unit tests that generate all manner of data as the name and one of those tests happened to pass an Array with between 2 and 50 entries which caused you to catch this bug. If so, nice work on those unit tests! If not, then you’re a mortal like the rest of us and a bug gets through from time to time.

As a fellow mortal I prefer to avoid writing these validations from scratch. Why? Because eventually you’ll end up with a custom validation library that you’ll be adding new features to and patching for a long time to come. Perhaps this challenge sounds appealing, but the added development time and bugs are going to detract from the velocity of a project. Instead, I’d recommend choosing an awesome open-source alternative like Joi. Not only will Joi make your team more productive, but you’ll also have less bugs, and more validation features available out of the box. Here’s what our previous validations code becomes after a conversion to use Joi.

const Joi = require('joi');

const countryCodes = Object.keys(require('country-codes'));

const userSchema = Joi.object({

name: Joi.string().min(2).max(50).required(),

country: Joi.string().valid(countryCodes).required(),

age: Joi.number().integer().positive().max(150).required()

});As with learning any new tool, there’s an initial ramp up period, but after a few hours with Joi you’ll be very comfortable and your team will probably favour it over writing chunks of custom validation code. The Joi syntax is arguably far more expressive than the 16 lines of code required previously too especially considering the fact that the previous code had 11 separate conditionals.

Updating our express route to use Joi and our created user schema is trivial.

const Joi = require('joi');

const users = require('lib/dao/user');

const countryCodes = Object.keys(require('country-codes'));

const userSchema = Joi.object({

name: Joi.string().min(2).max(50).required(),

country: Joi.string().valid(countryCodes).required(),

age: Joi.number().integer().positive().max(150).required()

});

route.use(require('body-parser').json());

route.post('/users', (req, res, next) => {

// validates and returns the user object on success

const ret = Joi.validate(req.body, userSchema, {

// return an error if body has an unrecognised property

allowUnknown: false,

// return all errors a payload contains, not just the first one Joi finds

abortEarly: false

});

if (ret.error) {

res.status(400).end(ret.error.toString());

} else {

// create a user using the

users.create(ret.value)

.then((result) => res.json(result))

.catch(next);

}

});Iteration #4 - Using Express Middleware

In a final attempt to make our code as clean as possible we might like to have the ability to add Joi validation for different parts of a request payload, such as req.query, req.headers or even req.params. For this I created an express middleware named express-joi-validation that makes doing so easy, but be sure to check out the other alternatives on npm too.

Here’s how you can use this middleware to validate a req.body of an incoming request:

// get an express-joi instance, parameters are optional

const validator = require('express-joi-validation')({});

const users = require('lib/dao/user');

const userSchema = Joi.object({

name: Joi.string().min(2).max(50).required(),

country: Joi.string().valid(Object.keys(require('country-codes')).required(),

age: Joi.number().integer().positive().max(150).required()

});

route.use(require('body-parser').json());

// express-joi-validation will automatically validate and return a 400

// error if req.body validation fails

route.post('/users', validator.body(userSchema), (req, res, next) => {

// If we're here that means req.body has been run through Joi and is valid

// req.originalBody is added by express-joi-validation. This contains the

// original body, before it was run through joi in the event you need it

users.create(req.body)

.then((result) => res.json(result))

.catch(next);

});If you need to validate headers you can do that too. Just remember, key names for headers are always lowercase in node.js.

const Joi = require('joi');

const validator = require('express-joi-validation')({});

const headerSchema = Joi.object({

// no auth token means no access!

'authorization': Joi.string().regex(/^Bearer [A-Za-z0-9]+/).required(),

// an api version must be specified

'x-api-version': Joi.number().valid(1.0, 1.1, 1.2, 2.0)

});

app.use(validator.headers(headerSchema));

app.get('/ping', (req, res) => {

console.log('headers before joi validations/conversion', req.originalHeaders)

// after conversion 'x-api-version' will be a number instead of string

console.log('headers after joi validations/conversion', req.headers)

res.status(200).end('pong');

})Performance Analysis

Some folks might point out that using a library to perform validations will inevitably have a performance impact. This is true, but with most software projects you need to find a balance of performance and data integrity you’re comfortable with so you should be prepared for this.

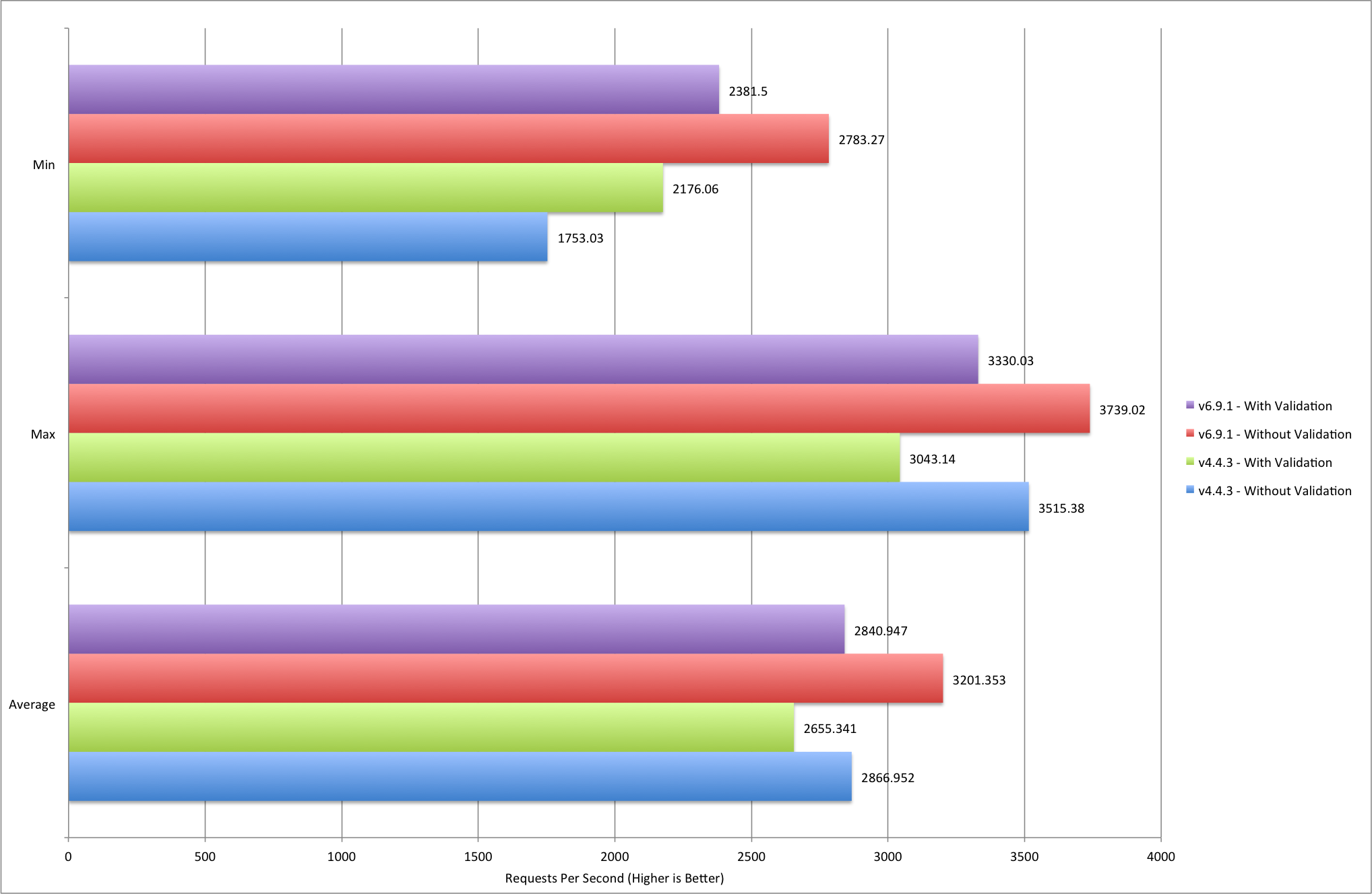

Out of curiosity I performed a load test on this sample application to determine what impact validations had across node v4.4.3 and v6.9.1. To test I used a script that performed 1000 requests with a concurrency of 100 to a single node.js process using Apache Bench. For the HTTP server Joi version 10.2.2 and express version 4.15.2 were used and all data is returned from process memory.

Note: Initially I tried 5000 requests at a concurrency of 100 but this produced somewhat inconclusive results. I assume this was due to frequent garbage collections

Here’s the test script. It prints the average requests per second for 10 load tests. Each load test is followed by a 5 second gap.

#!/bin/bash

x=1

while [ $x -le 10 ]

do

ab -n 1000 -c 100 -q http://127.0.0.1:8080/users?name=dean | grep -i "Requests per second"

x=$(( $x + 1 ))

sleep 5

done

Here are the details of the machine used to perform the test.

This first chart shows the average, min, and max requests per second for each combination of node.js and validations. Analysing this shows that the average throughput in node.js v6.9.1 is 11.25% lower when running our validations vs. when not running them. With node v4.4.3 we see roughly a 7.4% performance hit when running validations. Despite taking a larger performance hit from testing it’s worth noting that node v.6.9.1 with validations enabled is roughly on par with v.4.4.3 without validations. Min and max values show similar differences with v6.9.1 in the lead for each category.

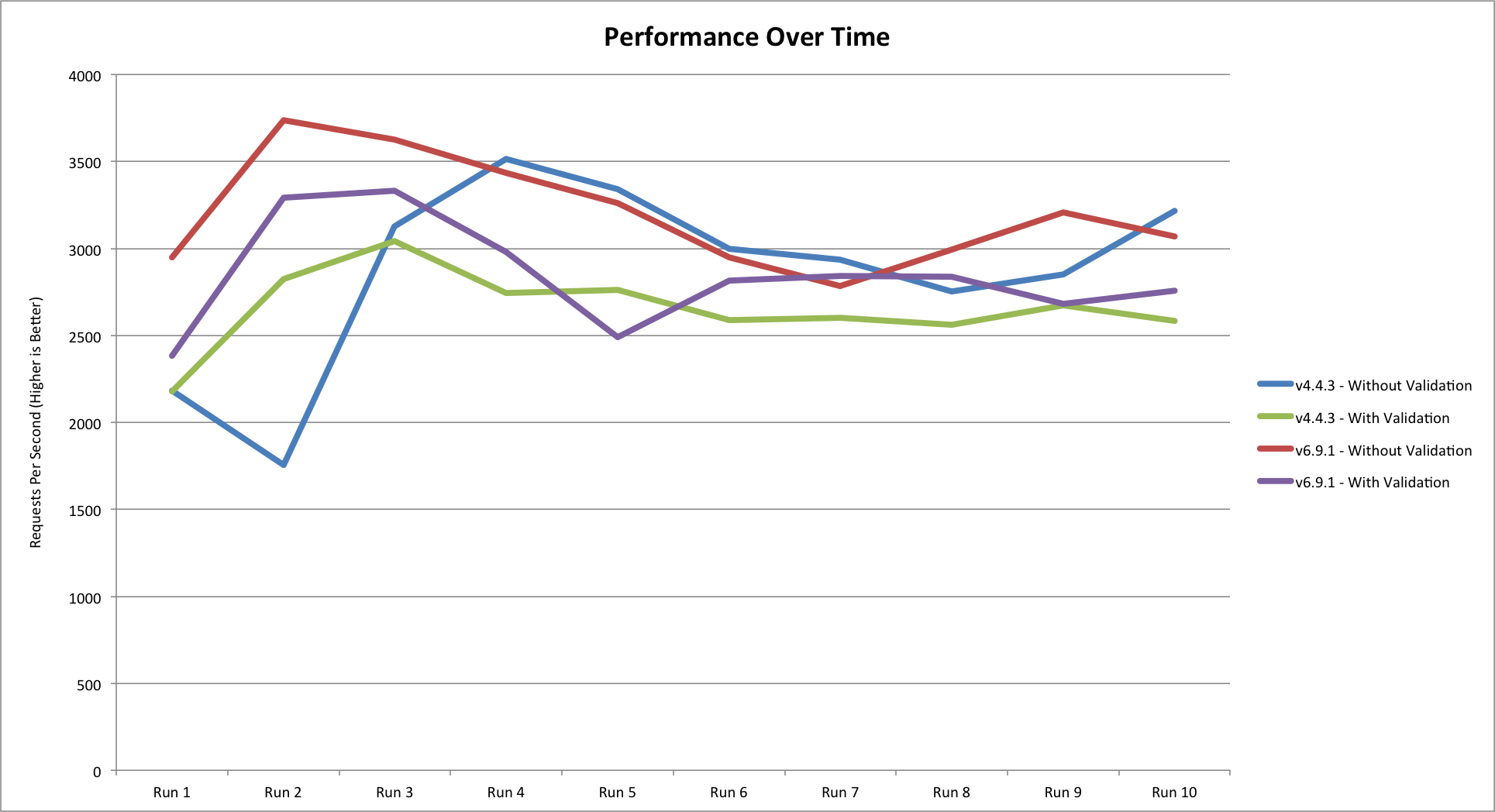

Below is a chart showing the average requests per second achieved over time. It demonstrates that the V8 JavaScript engine has a “warm up” probably due to its JIT design. After a few cycles it starts to show less erratic performance.

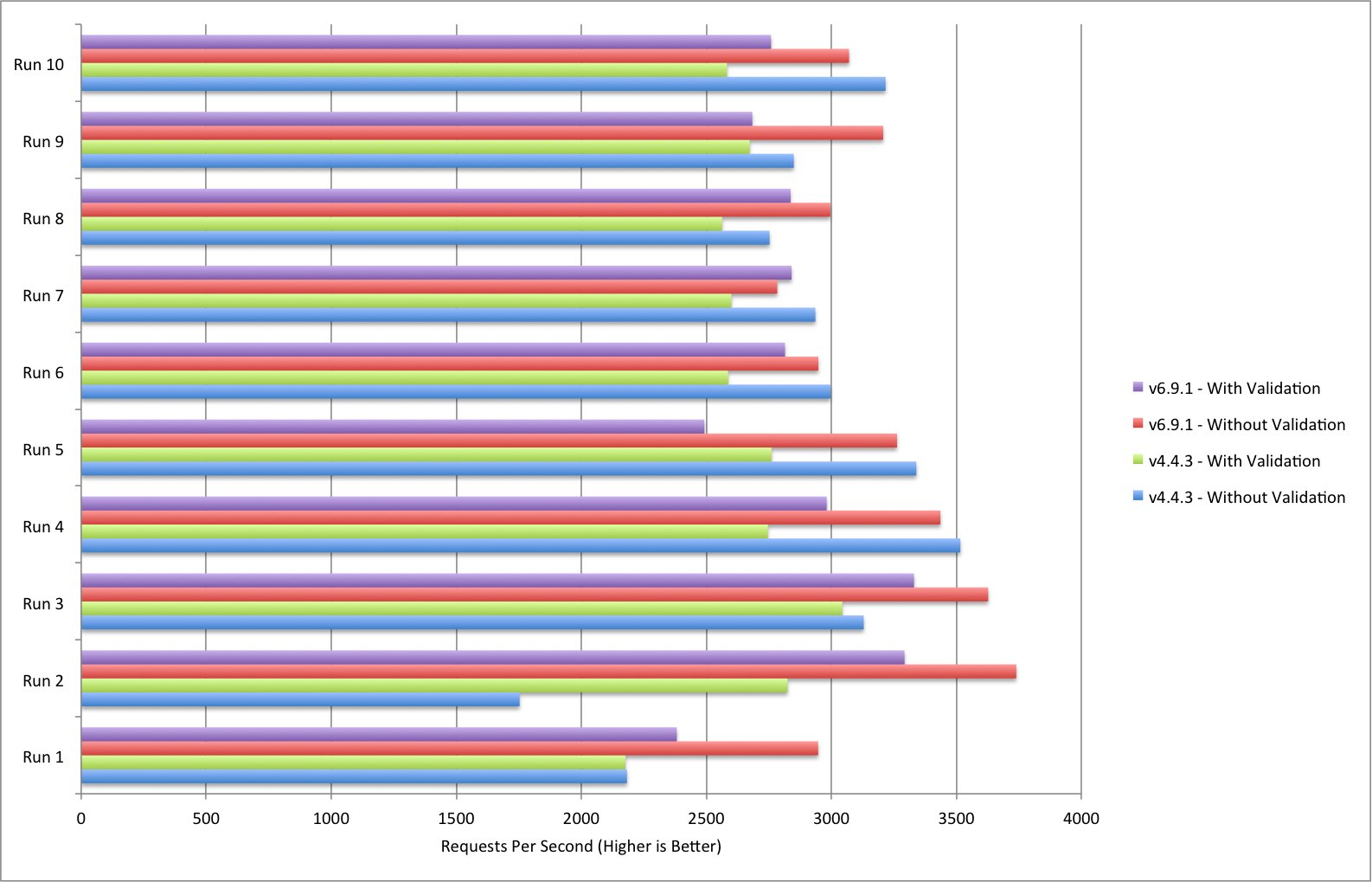

Last but not least is a chart containing all data captured as part of the test run.

Naturally, results might vary with different concurrency levels and more or less complex validation rules, but the overhead of validation for most applications is undeniably a cost you should accept and account for.

Summary

- Always validate and sanitise your inputs as best you can.

- Don’t write validations from scratch for serious applications without good reason.

- Decouple validation code from router logic when possible.

- Leverage node.js modules to quickly develop and integrate validations.

- Using Joi validations can add a 7% to 12% performance hit (or more) depending on your data and validations

- Load test frequently!

Evan Shortiss

Evan Shortiss