Unit Testing Express Routers

All code contained in this post is available here, with a more complex example available here.

Sometimes unit testing is a trivial affair, but that’s not always the case. In the past I found that I struggled when testing node.js applications built using express - specifically when it came to unit testing my routers. This isn’t a flaw with express, it’s simply the fact that it’s not immediately obvious what the best approach is, particularly when stubbing out dependencies is a requirement.

Supertest to the Rescue! Sort of.

Thankfully, the supertest library is available to assist us in our testing endeavours! Here’s an example that uses supertest:

describe('GET /ping', function () {

it('should respond with "pong"', function (done) {

request(require('./my-express-app.js'))

.get('/my-route/ping')

.expect(200, function (err, res) {

expect(res.body).to.equal('pong');

done();

});

});

});The example above demonstrates that we can pass our express application server to the supertest library, and thereby run tests against the server. This is awesome, but doesn’t come without challenges. For example, what happens in the scenario where we need to stub out dependencies that hit a live system, or that cause our tests to have a needlessly long execution time? We could use proxyquire, but that only allows us to stub dependencies one level deep. If we did that we would be stubbing out our routes, and not their dependencies that actually make the calls! Setting environment variables is another approach that might grant us some control, but this would become a deeply tedious manner of testing different paths throughout the codebase.

Inversion of Control

I’ve found that using inversion of control to mount express routers (instances of express.Router) to an express application object has turned out to be a fantastic method to simplify unit testing of my routes, and also make them easily configurable since I can pass variables into the creation of a route. What does this all mean? It’s best demonstrated using an example and a short overview, so bear with me.

Typically in an express application you might bind routes to an application object in your entry point file. This is the approach that’s often presented online in examples and tutorials, and is demonstrated below.

// file: main.js

var express = require('express');

var app = express();

var userRoute = require('./user-route');

// Mount user route to the express app, we specify "/users" as the path

app.use('/users', userRoute);If we were to invert this, we’d create a small module that exports a function, pass the express object into the function, and have the function bind an express.Router to the passed object. Here’s an example of that in action.

// file: main.js

var express = require('express');

var app = express();

var userRoute = require('./user-route');

// Have user route mount itself to the express application, we could pass

// other parameters too, such as middleware, or the mount path

userRoute(app);The difference is subtle, but it significantly improves our testing ability and makes routers configurable.

- The full mount path is defined on the router e.g “/users/:username” so we can detect if the route is mounted incorrectly in unit tests.

- Each invocation returns a unique router instance.

- Dependencies can be injected. This means a router is configurable, and reusable.

- Easier to mount routers uniquely to many express instances if required without clearing the require cache.

- Testing is simplified since we can create a unique router prior to each test without clearing the require cache.

Here’s an example module that creates a router and binds it to an injected express application.

// file: user-route.js

var express = require('express');

var users = require('./users');

module.exports = function (app) {

var route = express.Router();

// Mount route as "/users"

app.use('/users', route);

// Add a route that allows us to get a user by their username

route.get('/:username', function (req, res) {

var user = users.getByUsername(req.params.username);

if (!user) {

res.status(404).json({

status: 'not ok',

data: null

});

} else {

res.json({

status: 'ok',

data: user

});

}

});

};Testing

Below is a snippet that demonstrates how we can test our route in isolation from other components. It might appear to be complex at first glance, particularly if you haven’t used sinon or proxyquire in the past, and that’s fine! Take a read of the code and comments, then we’ll cover some of the statements in a little more detail below.

// We'll use this to override require calls in routes

var proxyquire = require('proxyquire');

// This will create stubbed functions for our overrides

var sinon = require('sinon');

// Supertest allows us to make requests against an express object

var supertest = require('supertest');

// Natural language-like assertions

var expect = require('chai').expect;

var express = require('express');

describe('GET /ping', function () {

var app, getUserStub, request, route;

beforeEach(function () {

// A stub we can use to control conditionals

getUserStub = sinon.stub();

// Create an express application object

app = express();

// Get our router module, with a stubbed out users dependency

// we stub this out so we can control the results returned by

// the users module to ensure we execute all paths in our code

route = proxyquire('./user-route.js', {

'./users': {

getByUsername: getUserStub

}

});

// Bind a route to our application

route(app);

// Get a supertest instance so we can make requests

request = supertest(app);

});

it('should respond with a 404 and a null', function (done) {

getUserStub.returns(null);

request

.get('/users/nodejs')

.expect('Content-Type', /json/)

.expect(404, function (err, res) {

expect(res.body).to.deep.equal({

status: 'not ok',

data: null

});

done();

});

});

it('should respond with 200 and a user object', function (done) {

var userData = {

username: 'nodejs'

};

getUserStub.returns(userData);

request

.get('/users/nodejs')

.expect('Content-Type', /json/)

.expect(200, function (err, res) {

expect(res.body).to.deep.equal({

status: 'ok',

data: userData

});

done();

});

});

});So what’s happening in this test? The supertest calls, that’s anywhere you see request.METHOD, are pretty digestible; you state the URL you want to make a request to, and then state your expectations. The real magic happens in the beforeEach. In this function we require our module, stub out it’s dependencies using proxyquire, create an independent express application instance, and pass that express instance to our module. This means we have a minimal express application that contains the current route we need to perform tests on, and no more. Had we simply required our application entry point we’d potentially have to ensure a number of environment variables are configured, deal with startup tasks, and find a way to stub out dependencies that are nested more than one level deep.

What’s proxyquire?

proxyquire is a replacement for the require statment (only for testing!) that allows you to provide a second argument that contains a hash, this hash maps require calls in the file being required (the first parameter) to stubs you’ve defined (the second parameter). Besides making testing easier, proxyquire also enables a developer writing tests for a route to continue doing so, even if a dependent module is unfinished. In our example above we don’t care if the users module is finished or not, we just need to know what its interface and return values will look like.

And sinon?

Using sinon to create stubs is not required, but is very useful since it’s a thoroughly tested, standard library that’s designed specifically with testing in mind. You could write your own stub functions, but being able to write stub.returns(‘hello, world’) is more concise, standardised, and immediately comprehensible.

Conclusion

As demonstrated it is relatively easy to test express routers in isolation, it just takes a little setup initially. In an agile environment this is beneficial since it reduces the dependency of one developer on another’s code while working on parallel stories and also makes it possible to produce more robust, tested code. Using a code coverage tool such as istanbul will allow you to immediately see where you’ve missed test coverage in your unit tests too.

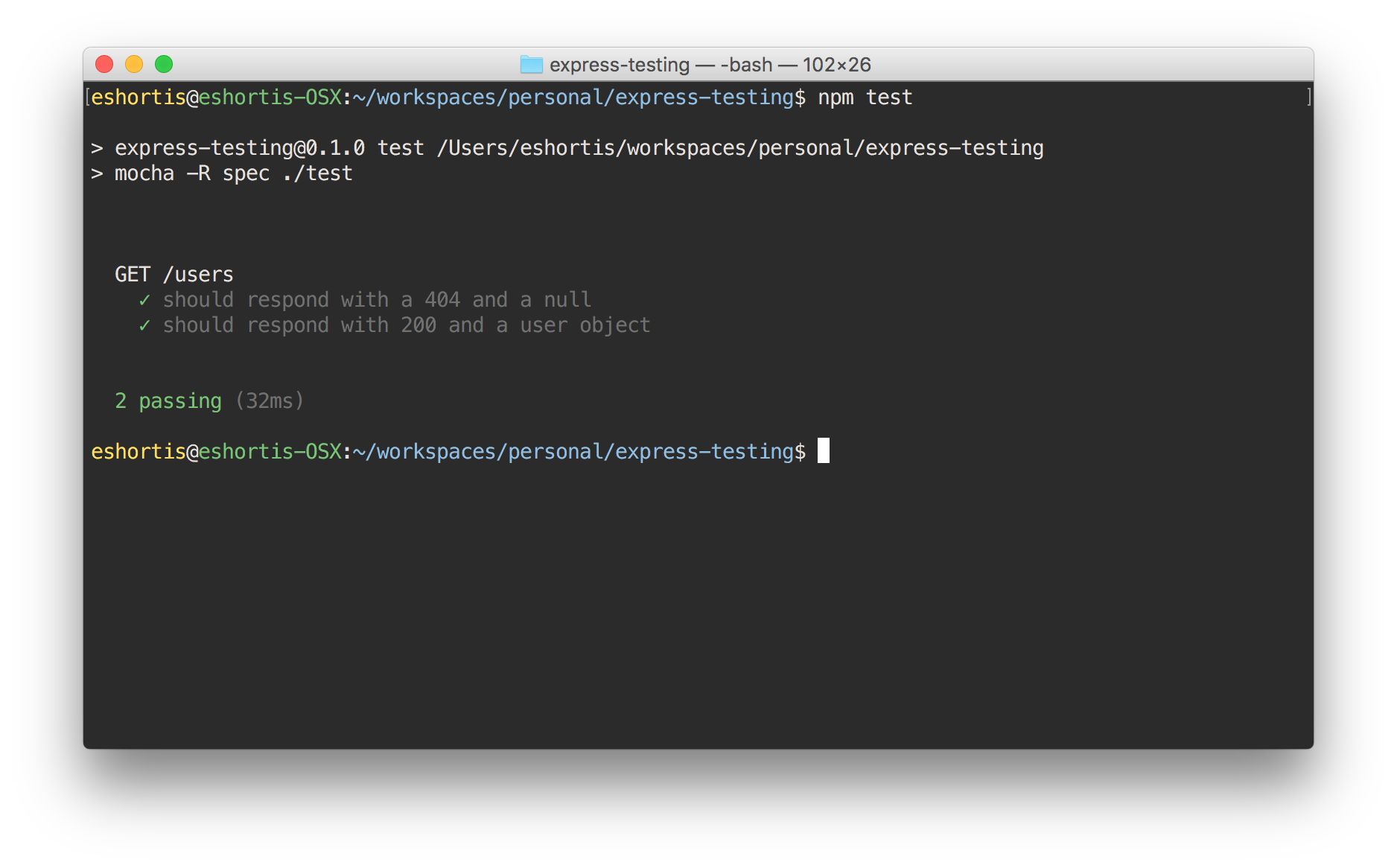

The image below is an example of the test output for the code above.

Evan Shortiss

Evan Shortiss